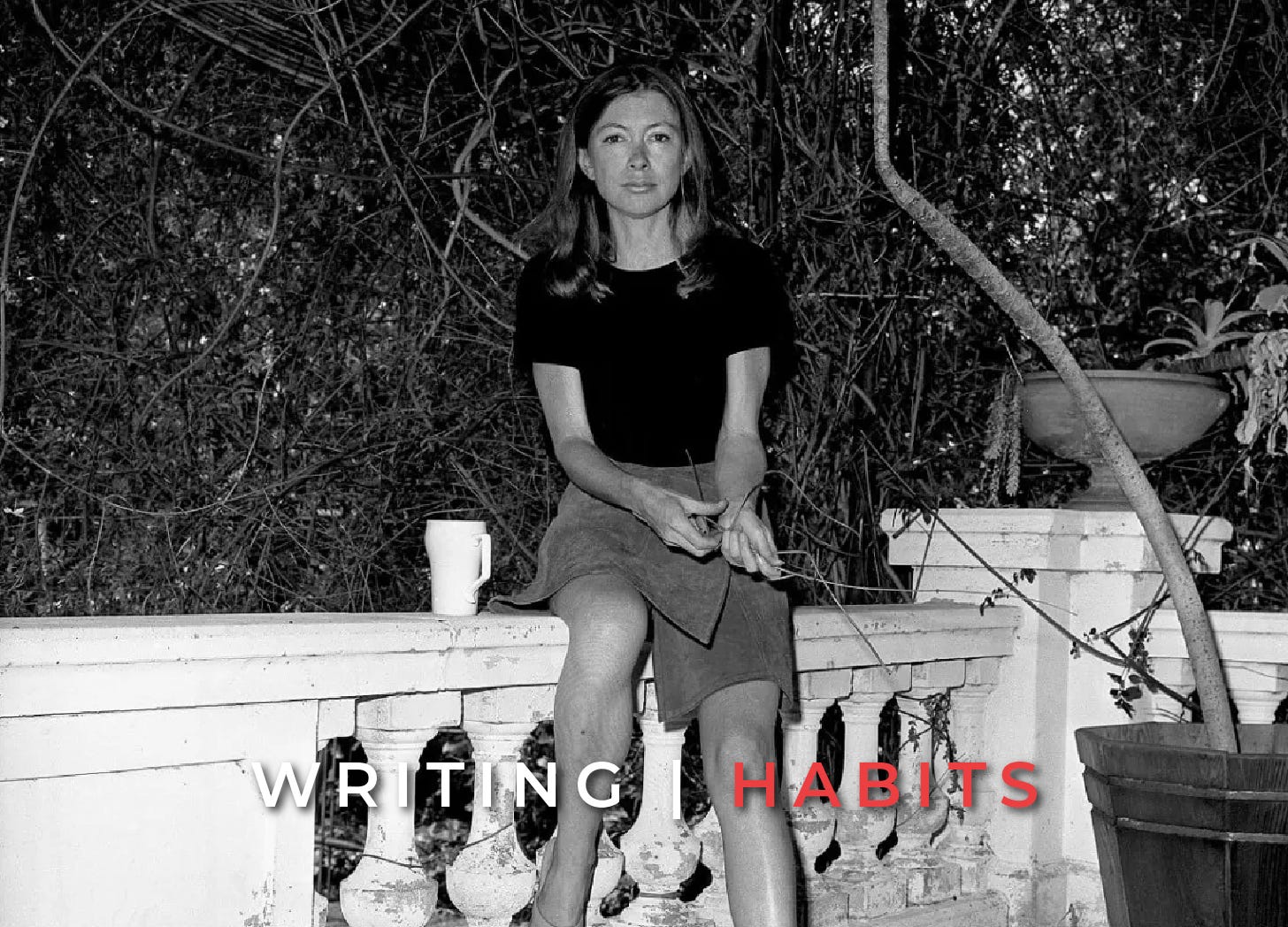

Joan Didion's Thoughts on Journaling

How the Practice of Recording Fragmented Memories and Imagined Truths Still Resonates in the Digital Age

Joan Didion’s essay On Keeping a Notebook, from her collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, may have been written in the 1960s, but its insights into the writer’s mind feel just as relevant—if not more so—in today’s world of blogs and tweets.

The impulse to write things down, she says, is less about recording facts and more about capturing fragments of the self, tracing the outlines of memory, or preserving an imagined truth that serves a deeply personal purpose.

Enjoy!

Know someone with a unique creative process? Drop their name in the comments—I’d love to feature them!

The Compulsion to Write Things Down

The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.

I suppose that it begins or does not begin in the cradle. Although I have felt compelled to write things down since I was five years old, I doubt that my daughter ever will, for she is a singularly blessed and accepting child, delighted with life exactly as life presents itself to her, unafraid to go to sleep and unafraid to wake up.

Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.

When Truth Isn’t the Point

So the point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking… In fact I have abandoned altogether that kind of pointless entry; instead I tell what some would call lies.

“That’s simply not true,” the members of my family frequently tell me when they come up against my memory of a shared event…Very likely they are right, for not only have I always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what merely might have happened, but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters.

A Notebook About Others—Or Just About Me?

I sometimes delude myself about why I keep a notebook, imagine that some thrifty virtue derives from preserving everything observed.

I imagine, in other words, that the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not. I have no real business with what one stranger said to another at the hat-check counter in Pavillon... My stake is always, of course, in the unmentioned girl in the plaid silk dress. Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point.

It is a difficult point to admit. We are brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves; taught to be diffident, just this side of self-effacing.(‘You’re the least important person in the room and don’t forget it,’ Jessica Mitford’s governess would hiss in her ear on the advent of any social occasion; I copied that into my notebook because it is only recently that I have been able to enter a room without hearing some such phrase in my inner ear.)

Only the very young and the very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favorite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creek near Colorado Springs.

The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people’s favorite dresses, other people’s trout.

The Implacable “I” of Notebooks

[O]ur notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable “I.”

Keeping in Touch with Our Former Selves

I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.

We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.

I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be; one of them, a seventeen-year-old, presents little threat, although it would be of some interest to me to know again what it feels like to sit on a river levee drinking vodka-and-orange-juice and listening to Les Paul and Mary Ford and their echoes sing “How High the Moon” on the car radio.

[…]

It is a good idea, then, to keep in touch, and I suppose that keeping in touch is what notebooks are all about. And we are all on our own when it comes to keeping those lines open to ourselves: your notebook will never help me, nor mine you.

Subscribe to Writers Are Weird

Access the full archiveDocumenting the creative process. Created by Sam Mas.